Joseph Robinson

Joseph was born on the 20th April 1889 in Welton, the son of Robert and Jane Robinson (nee Tuxford), who at the time of the 1901 census were living at Low Farm, Cammeringham, where his father was a farm foreman. Joseph was one of eight children in the family, the youngest of these, Florence, had been born in Barkwith where Joseph’s grandparents (Frederick and Catherine Robinson) lived. Joseph had been educated at East Barkwith School.

His father, Robert, lied about his age saying he was 38 years old (he was born in 1869 so was actually 46) to enlist on the 21st May 1915, serving with the 3rd Battalion Lincolnshire Regiment. He was discharged as medically unfit a year later on the 24th May 1916, due to an old injury that had occurred prior to joining up. Joseph’s three brothers all also saw active service during the war.

Joseph enlisted right at the start of the war on 11th August 1914, leaving his job as a guard on the Great Central Railway at Lincoln and joining the 1st Battalion of the Coldstream Guards who were stationed in Aldershot, Hampshire as part of the 1st (Guards) Brigade of the 1st Division. He embarked for France on the 24th November 1914, just in time for the onset of winter on the Western Front.

In May 1915 the battalion were involved in The Battle of Aubers Ridge, a British offensive that turned into a significant disaster for the British army. No ground was won and no tactical advantage gained. The attack was launched following a short bombardment of German positions, that failed to do much other than to alert the enemy that an attack was imminent. Many of the attackers were machine gunned either climbing out of their trenches or bunching up around the few holes that the short bombardment had blown in the German barbed wire.

By mid-June the 1st Battalion were in the Cambrin defences close to the town of Bethune, and on the 13th June moved up (without casualties) to relieve troops in trenches near Cuinchy (possibly at Auchy-la-Bassée). The battalion war diary indicates that the big guns of both sides were shelling each other’s trenches, day after day at this stage. On the 14th June when Joseph is recorded in the records as having died, the only entry in the war diary says ”A great deal of shelling by our own guns. Battalion HQ shelled by pip-squeaks but no damage done”. A note in the margin records that one ‘other rank’ was wounded that day and that another one was missing.

It’s not surprising that in the chaos of war in the trenches, accurate information was not always captured. It’s likely that Joseph was the missing man recorded in the war diary on the 14th and his status was later updated to having been killed in action. Two men with links to Barkwith had been lost within a month. At home in Britain the true horror of life in the trenches was starting to be realised and recruitment was becoming more difficult.

Albert Edward Russell

Albert Edward Russell was born at East Barkwith in 1896, the son of William and Julia Russell. William was a wheelwright, born in Fulstow, while his wife, Julia, was from Benniworth. William and Julia has five children, all but the eldest, born in East Barkwith.

Albert was baptised 3rd December 1896 in East Barkwith.

When he enlisted on the 2nd March 1916 he was living at the Railway Inn, Donington on Bain, and gave his profession as ‘groom’. He initially enlisted in the Lincolnshire Regiment and was called up for service on the 28th August 1916, but on the 31st October 1916 he was transferred to the Machine Gun Corps, where he undertook further training. On the 17th December, he returned to camp six hours later than his pass allowed and was docked three day's pay.

He went overseas with the 2nd Battalion on the 9th January 1917.

He married Mabel Russell (nee Bonner) on the 7th June 1917, following the birth of their son James Albert Russell on the 19th April. Mabel (see picture) later lived at 14, Sussex St, New Cleethorpes.

On the 4th May 1917 he was admitted to 22 general hospital with gunshot wounds to the left leg and right buttock, then on the 12th May transferred to the war hospital in Edinburgh. Afterwards he continued to suffer some weakness in his left leg when walking any distance, possibly due to shrapnel remaining within it.

He returned overseas to France on the 13th January 1918, and served temporarily as a Lance Corporal between the 18th May and 27th September, before reverting to being a Private on admission to 18 General Hospital with cardiac problems after having been kicked by a mule.

He was in Huddersfield War Hospital from the 6th-14th December 1918, before being transferred to the cardiac centre at Leeds Royal Infirmary, where he remained until the 26th January 1919. He was demobilised from the army on the 23rd February 1919, classed as being 20% disabled from his gunshot wounds. On the 8th April 1919 Albert was living at 37 Henley Street in Lincoln.

The family moved to 14 Sussex Street, New Cleethorpes and a second son, Walter Russell, was born in 1921.

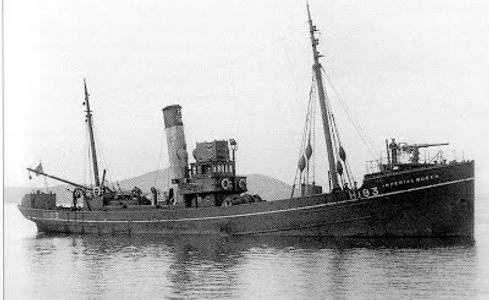

Albert joined the Mercantile Marine, working as a Deck Hand on the Imperial Queen.

The Imperial Queen had been built by the Dundee Ship Building Co for The Great Northern Steam Fishing Co of Hull in 1914. She had been requisitioned in May 1915 and converted into a mine sweeper, fitted out with Hydrophones and armaments comprising 1-12pdr, 1-7.5" Bomb Thrower (Howitzer). Following the war she was returned to her owners in 1919.

The ship disappeared with all hands, including Albert, on or around the 28th July 1920 and ironically is believed to have struck a mine.

The picture on the left shows the skipper and crew of the Imperial Queen, although Albert does not appear (judging by the ages of those present) to be present on this photograph.

Albert is remembered on the Tower Hill Memorial in London which commemorates men and women of the Merchant Navy and Fishing Fleets who died in both World Wars and who have no known grave. It stands on the south side of the garden of Trinity Square, London, close to The Tower of London.

As Albert died after the war ended and following his demobilisation from the army, he is not commemorated on the Barkwith war memorial, but is included here as another individual from the parish who served and was eventually killed as a result of the war.

Mabel remarried in 1926 and was buried at St Mary’s in Hainton, following her death in 1976.

Edward Allen Smeathman Hatton

Edward was born in West Barkwith, the son of the Rev. John Leigh Smeathman Hatton and Mrs. Edith Martha Neck Hatton (nee Hammerton). His father was the Rector of West Barkwith at the time of the 1891 census. Edward’s parents, married on 21st September 1881, and had moved into the area, his father being from Liverpool and his mother from Colchester.

Edward had three older half brothers, John, Francis and Charles, from his father’s first marriage to Lois Caroline Marsh. Lois died in August 1880 in Scarborough. His eldest brother, John, studied at Oxford, on the 1891 census was listed as ‘demonstrator of physics, Oxford’, practised as a Barrister and by 1911 was Principal of East London College. The next eldest, Francis served in the Lincolnshire Regiment before the First World War, and was assigned to the Niger Constabulary when he died of fever at Asaba (Headquarters of the Niger Constabulary) in West Africa on the 8th July 1898. At one time there was a plaque commemorating him in East Barkwith church, which read “IN LOVING MEMORY OF / FRANCIS HENRY SMEATHMAN HATTON / CAPTAIN 4TH BATTALION LINCOLNSHIRE REGIMENT / AND ROYAL NIGER COMPANY'S SERVICE / SECOND SON OF REV. LEIGH S. HATTON B.A. SOMETIME RECTOR OF THIS PARISH / BORN 3RD JULY 1868 = DIED OF FEVER AT ASABA / NIGERIA WEST AFRICA 8TH JULY 1898”. This plaque is now held by Lincolnshire Museums Service.

Edward also had a younger sister Lois Caroline, and two younger brothers Frederick and Horace, all born in West Barkwith. Their father, John Leigh Smeathman Hatton, died in West Barkwith on the 5th October 1894, of heart disease asthenia (Da Costa’s syndrome). Edward was 10 years old.

After their father’s death, the family moved and in 1901 Edith and her four children were living at 32 St Michael’s Road, Bedford. Edward, then 17, enlisted in the Royal Marine Light Infantry and spent the next year in college before joining the Chatham Division in July 1902. By December of that year he was being described as “a promising young officer”, and in 1904 as “a zealous, capable young officer who only wants experience to make him useful”.

From October 1904 to December 1906, Edward served on HMS Victorious, a British battleship of the Majestic class, built in Chatham dockyard and launched in 1895. During that time the Victorious was second flagship of the Channel Fleet, which became the Atlantic Fleet in January 1905. His reports during this time repeatedly described him as zealous and of good physical fitness.

After a number of short assignments to other ships, the 1911 census recorded Edward onboard HMS Penguin operating out of Sydney, Australia. He served on HMS Penguin from July 1909 until February 1912.

That was followed by a number of short assignments, before at the outbreak of the First World War, landing with the Chatham Battalion at Ostend on the 26th August 1914. After a short stay they re-embarked on the 1st September and were landed at Dunkirk on the 20th September. Between 4th – 9th October they were in action near Antwerp, before embarking again at Ostend on the 11th October.

On the 6th February 1915 Edward and the rest of the Chatham and Plymouth Battalions, embarked at Plymouth as part of the advance force of the Royal Naval Division sailing for the Dardanelles. The Chatham Battalion were onboard HMT Cawdor Castle. After a short stop at Port Said in Egypt, between 29th March – 7th April, they continued on and landed at Gaba Tepe, Gallipoli on the 28th April 1915, to provide temporary relief for some of the Australian units who had been involved in the initial landings on the 25th.

On the 29th April Edward died, an excerpt from despatches saying he was “killed while most gallantly leading a counter attack against one of our trenches which had been occupied by the Turks, about 6:00 pm 29/04/1915 at Gaba Tepe, Gallipoli peninsular”.

He is buried in the Beach Cemetery, Anzac, Turkey.

Following his death a marble plaque was made and placed in All Saints Church in West Barkwith where his father had been Rector. The text on the plaque says “In Loving Memory of Edward Allen Smeathman Hatton Captain Royal Marine Light Infantry Fourth Son of Rev. J. Leigh S. Hatton BA, Sometime Rector of this Parish, Born 29th October 1883 Killed in Action in Gallipoli 30th April 1915” The date on the plaque of the 30th April was actually the day Edward had been buried, rather than the date of his death. The plaque is now held by the Museum of Lincolnshire Life.

Horace Walter Smeathman Hatton

Horace was another son of the Rev. J. L. S. Hatton and Mrs. Edith Martha Neck Hatton (nee Hammerton), who lived at West Barkwith Rectory. His father was the Rector of West Barkwith at the time of the 1891 census. His parents, married on 21st September 1881, and had moved into the area, his father being from Liverpool and his mother from Colchester. Horace was born on the 13th March 1889 in West Barkwith and baptised in All Saints Church on the 14th April. His father, John, died five years later on the 5th October 1894.

After his father’s death, the family moved and in 1901 Edith and her four children were living at 32 St Michael’s Road, Bedford. Horace later moved to 30 Percy Gardens, Teignmouth, Devonshire.

By the time Horace enlisted, the family had already experienced the loss of both his older half brother (Francis) who had died of fever while serving with the Niger Constabulary in West Africa in 1898, and his older brother (Edward) who had been killed in action in 1915 while fighting the Turks at Gallipoli.

Horace served with the 2nd Battalion, South Staffordshire Regiment. In August 1918 the battalion were engaged in trench warfare at Ablainzevelle in France. A British attack on the 22nd captured Courcelles-le-Comte and on the 23rd the battalion moved up ready for an attack on Ervillers at 11am.

The battalion attack commenced following an artillery barrage of the enemy positions. It was observed that some German troops were retreating and others readily surrendered, however there was still significant resistance from some outposts, including sniper and machine gun fire. Some dugouts were taken in hand-to-hand fighting while others were blown-up. While waiting for the artillery barrage of Ervillers to lift, one company flanked the village and were able to capture a field gun and twenty machine guns. The company then occupied the high ground south-east of the village.

When the artillery barrage lifted the rest of the battalion advanced on the village encountering heavy machine gun fire, which was silenced by the lewis guns, then a strongpoint where fifty German soldiers were eventually captured. Following a brief pause for re-organisation the troops advanced into the village where they met and overcame considerable resistance, capturing about seventy of the enemy along with machine guns, trench motors and four field guns.

The action was a success but the war diary notes a number of officer casualties including Captain H W S Hatton, who had been killed. Horace is buried at Douchy-Les-Ayette British Cemetery, France (see picture). He left his estate to his mother, Edith.

Walter Smith

Walter, the son of Henry and Lucy Smith of West Barkwith, is listed in the 1911 census as a ‘Labourer in nursery’. He was one of four children listed on the census as living at home in West Barkwith (three boys and a girl), although his parents had eight children in total. His father, Henry, was a ‘road-man’ or ‘labourer on the highways’.

When Walter enlisted in May 1915, the 6th Battalion Lincolnshire Regiment were based at Frensham, near Farnham in Surrey. The battalion was mobilised for war on the 1st July 1915 and sailed from Liverpool via Alexandria and Mudros, to Gallipoli.

After involvement in the amphibious landings at Suvla Bay and the battles afterwards, the badly mauled battalion moved to Egypt, where it is likely that Walter having completed basic training joined them. Following a spell on the Suez Canal defences, the 6th Battalion arrived at Marseilles on the 8th July and disembarked the next day, moving to Carcassone Camp (Marseilles). From there they travelled by train and foot until on the 19th July they entered the trenches near Arras. Over the next few weeks they endured gas alarms, enemy raids and took regular casualties from trench mortar bombardments.

In September they were once again in the trenches, this time near Ovillers. Again they experienced shelling, attacks and counterattacks, taking further casualties until relieved on the night of the 19th September. For much of the rest of the month they were held in reserve.

During October the battalion received a new draft of men and spent much of the time carrying out training near Beaucourt.

During March 1917 the battalion were in the Authie valley working on the railway, before moving during April to Haplincourt where they remained for a month on a relatively quiet part of the front line. In mid-May the battalion moved again and started preparing for an attack the objective of which was a group of hills known as the Messines-Wytschaete Ridge. The attack, planned for the 7th June was to include an extraordinary event, the explosion of nineteen deep mines (of an original planned twenty two) at the moment of assault. The construction of the mines had begun eighteen months earlier, involved the digging of eight thousand yards of gallery and they had then been populated with over one million pounds of explosives.

At dawn on the 7th, with officers and other spectators watching from the hills, there was a sudden rumbling of the earth and huge flames shot up, accompanied by clouds of smoke, dust and debris. The explosion (see picture), probably the largest deliberate man made explosion the world had seen at that time, is believed to have killed some 10,000 enemy troops. This was followed by the start of a heavy barrage. In the afternoon the battalion advanced encountering very little opposition, the enemy either running or surrendering until the objective was nearly reached. At that point the Germans tried a counter-attack but with the help of tanks it was broken up and the objective gained with only light casualties. The battalion were subjected to heavy shelling and further counterattacks but held their position. By the end of The Battle of Messines, they had lost 6 officers and 160 other ranks.

Between the 1-15th July 1917 the 6th Battalion was engaged in training at Northleulinghem. The battalion moved to front-line trenches on the 17th July. At that point, the enemy lines were so close that when the Allied guns shelled the enemy’s trenches the battalion had to temporarily leave their trenches. The Germans retaliated with frequent gas shells, resulting in the battalion spending several nights wearing their box respirators.

On the 22nd August they attacked heavily fortified enemy positions including a large and strongly held ‘pillbox’ at Bulow Farm, situated among a group of smaller fortifications. The attack was successful and well carried out, but the battalion took a number of officer casualties (including Lieutenant Henry Allen Maynard Denny from East Barkwith, who was wounded) and amongst the other ranks, nineteen were killed, sixty-three wounded and two missing. The 6th Battalion were present at The Battle of Poelcapelle on the 9th October 1917, but were not called to attack, instead spending two days in shell holes under heavy shelling.

The winter through to March 1918 brought miserable weather, making life in the trenches extremely hard for the men of the battalion. The battalion trained at Vaudricourt until the 24th of January, when their brigade took over the Hulluch sector and the battalion moved into support trenches.

The battalion spent the majority of the spring and summer 1918 in the line near Loos. Then on the 25th of August they moved to- La Thieuloye (twenty miles north-west of Arras) taking over forward positions on the night of the 30th August. They were part of the advance during The Battle of the Drocourt-Queant Line on the 1-2nd September and then remained in that area, until the 20th September.

The 6th Lincolnshire, were in support during hard fighting at the Canal du Nord, near Sains-lez-Marquion then moved to Cherisy on the 25th September. They moved a number of times in support of attacks over the following few days until on the 2nd of October they took over dug-outs west of Haynecourt.

On the 5th of October the battalion started moving forward, occupying the village of Aubencheul and establishing themselves along the eastern banks of the Canal de la Sensee before daylight on the 7th. Later that day they again advanced, following a retreating enemy to take up a position on the high ground south-west of Hem-Lenglet and north of Abancourt. They encountered significant shell and machine-gun fire during the advance, taking casualties of two officers and ten other ranks killed or wounded. On the 10th October following a successful daylight reconnaissance of Hem Lenglet, the 6th Lincolnshire and 7th South Staffordshire launched a night attack and captured the village.

Although the attack was very successful, Walter was killed in action. Having survived through so many battles, he died just a month before the war ended and is buried in Naves Communal Cemetery Extension.

Had Walter had chance to look at the graves in the Hem-Lenglet cemetery, he might have seen that of John Green, another Barkwith resident who had died and been buried there the previous year.

Tom Weatherhog

Tom, born in Sotby on 11th August 1886, son of John Weatherhog, came from a long line of Blacksmiths. He married Ellen Jackson in February 1908 and had two daughters, Margaret Ellen, born in March of that year and Emily May born in 1909. In 1911, Tom, Ellen and Emily were living in Washingborough with Tom working in a foundry, while three year old Margaret was recorded as living with her grandparents in Sotby. In 1915 he enlisted in the Royal Artillery at a time when men with knowledge of horses were in severe demand on the western front.

The Royal Regiment of Artillery during the First World War was made up of three elements:

- The Royal Horse Artillery: armed with light, mobile, horse-drawn guns that in theory provided firepower in support of the cavalry and in practice supplemented the Royal Field Artillery.

- The Royal Field Artillery: the most numerous arm of the artillery, the horse-drawn RFA was responsible for the medium calibre guns and howitzers deployed close to the front line and was reasonably mobile. It was organised into brigades.

- The Royal Garrison Artillery: developed from fortress-based artillery located on British coasts. From 1914 when the army possessed very little heavy artillery it grew into a very large component of the British forces. It was armed with heavy, large calibre guns and howitzers that were positioned some way behind the front line and had immense destructive power (www.1914-1918.net)

Although Tom’s regiment is recorded by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission as being the Royal Field Artillery, it appears that he was actually serving with the Royal Horse Artillery (B Battery, 15th Brigade). He enlisted in April 1915.

Tom’s rank is given as ‘Shoeing Smith’, which was a specialist trade within the British Army. Until the phasing out of horse transport after WWI, in addition to cavalry & artillery regiments, engineers, ordnance and service Corps all had farriers & shoeing smiths amongst their ranks. A Shoeing Smith could shoe horses, typically would understand the problems associated with horses’ feet and legs, and could perform blacksmith work.

Each Royal Horse Artillery battery would be equipped with six 13-pounder field guns and have five officers, two hundred men and two hundred and twenty eight horses.

The brigade was in Egypt defending the Suez canal at the start of March 1916, before sailing from Alexandria to Marseille aboard the SS Huanchaco, then travelling by train to Pont Remy near Abbeville to join the fighting on the western front.

The brigade moved to Rue St Barbe on Arras on the 28th March 1917 and started constructing positions. This work continued over the next couple of days, until on the night of the 30th, they were able to put the guns in position and start storing ammunition with them. Work then continued on improving the positions in preparation for a four day bombardment to support an upcoming attack on enemy trench systems. From the 1st April, these preparations continued under shell fire from the Germans, with the brigade taking casualties on the 1st, 2nd and 3rd April.

The battalion’s war diary for the 4th April 1917, at Rue St Barbe, Arras, mentions Tom, saying “4.4.17. V Day. Batteries fired according to programme. No. 99463 S/S Weatherhog killed and No. 85649 Dr. Elgan wounded by HE, both of 'B', RHA.”

Tom is commemorated in France at the Faubourg D’Amiens Cemetery in Arras.

His uncle (John’s brother), also called Tom Weatherhog, lived in East Barkwith, until he died in April 1930.

In 2006, Tom’s great granddaughter, Ann, was living in Sydney, Australia.

Arthur Wynne Williams

Arthur Wynne Williams was born in 1893 at East Barkwith, the son of Robert Owen Williams and Clementina Eliza Williams. Robert, originally from Wrexham in North Wales, and Clementina from Manchester, had married in 1885.

In 1891, Robert and Clementina were living at number 1 Albert Road in Stamford, with their three children, Eira Knight Williams, Elsie M Williams and Roderick Esmore Williams, along with a domestic servant. Elsie and Roderic had both been born in Stamford, while Eira, the eldest, had been born in North Wales prior to them moving.

The family moved again soon afterwards and Arthur was born in East Barkwith. He was baptised in the village on the 17th June 1893. In 1901 the family was living in Panton, where Arthur’s father, Robert, worked as a Landowner’s Agent.

By the time of the 1911 census, Arthur’s parents were living in Lincoln at Hartley Lodge, with Robert listed as being a Land Agent and Surveyor. Arthur was not living with them by that time, although his older sister, Eira Knight Williams, was. The family had two domestic servants, a cook and a housemaid.

Arthur emigrated to Canada, sailing to Montreal from Liverpool on the 14th June 1912 aboard the Tunisian (see picture), operated by the Allan Line Steamship Co Ltd. He stated his occupation as being a labourer. The Tunisian, the ship on which Arthur had travelled to Canada, was one of several ships that following the outbreak of war, transported the hastily assembled Canadian Expeditionary Force to England. The Tunisian was later anchored off the Isle of Wight and served as a prison ship for German prisoners of war.

Soon after the war started, Arthur enlisted on the 23rd September 1914 at Valcartier in Quebec. The Denny brothers (Robert and Maynard) from East Barkwith, also enlisted on this day in Valcartier with the same regiment, the 16th Canadian Infantry Battalion (Manitoba Regiment), so it has to be presumed that they had met up and were together.

The regiment sailed for England on October 3rd, 1914, then subsequently to France on the 12th February, 1915, disembarking at St. Nazaire three days later. Following indoctrination in trench warfare they relieved the 2nd Border Regiment south of Fleurbais. In mid-April the Canadians relieved a French Division in front of Ypres. The 16th Battalion took part in the Second Battle of Ypres during April 1915.

On the 7th August 1918, the battalion was at Boves, preparing to launch an attack the next day, in front of Amiens. The 3rd Brigade, including Arthur and the 16th Battalion, were to be involved in the initial assault.

On the 8th, the men assembled in the trenches ready for zero hour at 4:20am. Despite the noise made by the tanks, the attack took the enemy by surprise. The men moved forward in the early morning light, surrounded by a ground mist, which following an artillery barrage of the enemy trenches, was augmented by smoke. Minimal resistance was initially encountered with many of the enemy surrendering, allowing the capture of an anti-tank gun and several trench mortars. The battalion’s war diary does note that small parties of the enemy were encountered, one being at Hangard copse near where Arthur is buried.

Despite running into more determined resistance in parts, the overall attack was a success, capturing 18 artillery pieces, 17 trench mortars, 30 machine guns and over 900 prisoners. The regiment had 2 officers and 36 other ranks killed, including Arthur.

Arthur is buried at Hangard Communal Cemetery Extension, near Villers-Bretonneux. The original extension to the communal cemetery was made by the Canadian Corps in August 1918. It consisted of 51 graves in the present Plot I.

Arthur is also included on the memorials at North Collingham All Saints Church.